The story of the ultramarathon in the frozen Oymyakon has a rather complicated ending. Earlier, I talked about the idea, preparation and adventures, and then about the cold and equipment.

Day X

I went to bed at midnight. But I didn’t fall asleep. The thought that the next day I would do something no one had ever done before was very encouraging. I was tossing and turning from side to side, and scrolling through my mind about possible force majeure scenarios and ways of dealing with them. Then I realized I was going to fight the three “hippopotamuses”.

And here they go: Hypothermia, Hypoxia and Hypoglycemia! Hi there!

Each of these beasts can easily stop any runner who is not ready to meet them. And all three attack your brain first, not the body, and this can lead to some reckless actions. The things that pop into your head the night before the start …

To avoid getting worked up, I decided to visualize, to imagine the race in detail. Here I start, here I eat gels, change the mask. At 42 km, I understand that I have power enough for 50 km, the thermometer shows -60°C (-76°F), I run and run, I’m cold, but I’m willing to take it, and here I cross the finish line. Everything is going to be okay, everything is going to be okay … Here I start, here I eat gels, … And so my thoughts floated in circles all night.

Start

That night I never fell asleep.

The morning was fresh. The thermometer showed -59°С (-74.2°F). Here it was the cold front, as they had forecasted. We got up at six, had breakfast, packed our equipment. WE got dressed and got out ready to go. See how precisely we did everything? A real pleasure to look at. Not as the first time …

The guys attached the camera onto the windscreen of the bukhanka, fixed the thermometer to the side mirror, loaded up the provisions, equipment, gear, and drove to the start — the “-71.2°С” stele in Tomtor.

The director of the local museum brought me some pancakes so that I could appease the mighty Yakut spirit. I put the pancakes under the star and I prayed all the spirits, not just the omnipotent one, to help me cope with the race, and I also prayed for Eva’s recovery.

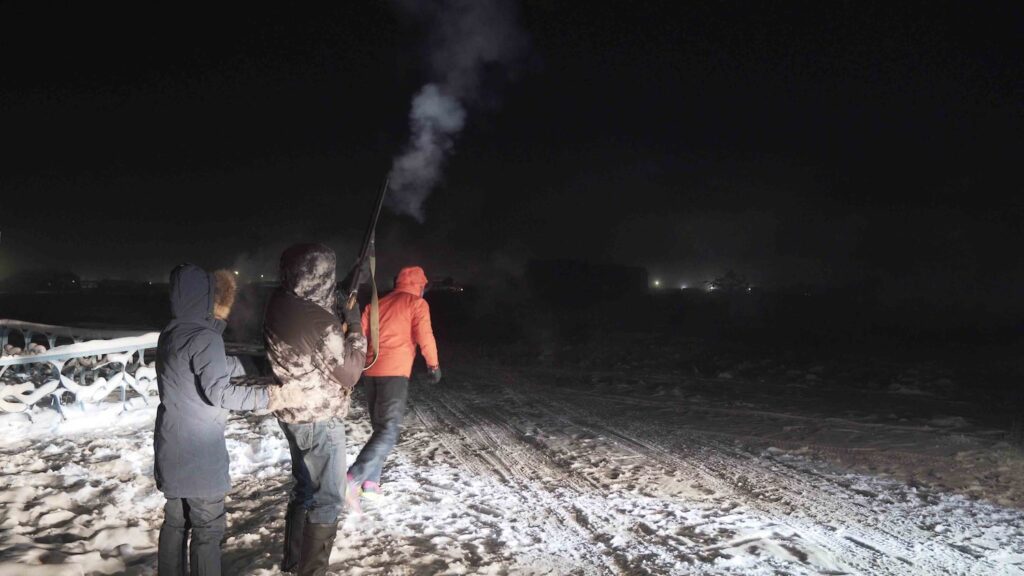

We are all on the spot: Sasha, Andrey, Vanya with his flare gun, deputy head of Tomtor — Ekaterina and the driver Afanasiy ? And my three “hippopotamuses” await me somewhere on the track.

The guys rushed like mad — Sasha carried the equipment and set up the cameras, and Andrey checked the equipment, food and clothes. They anointed my face with polar ointment (first Katya — she did it gently, and then Andryukha — roughly) and wished me good luck. Touch wood!

I know it’s supposed to avert bad luck, but there is no wood here to touch. Anyway, I’m doing it in my mind and take a look at my watch. We got to start. Countdown! 5,4,3,2,1! Bang!

Vanya took the flare gun, and here a red rocket soars into the cold dark sky. Somewhere down below, on the outskirts of the village of Tomtor, a tiny figure of a man wearing a thin orange jacket begins his race, to which he has walked all his life through straight and roundabout paths. Oh, if only the rocket could hear his thoughts …

— Where the heck am I supposed to run? Just can’t see anything before my eyes! Where’s that motherchucker car in front, darn it!

Its pitch-dark all around. And here is the car— it’s out there, right in front of me. I am running. I already have a flashlight on my head, headlights in the back, and safety lights ahead. Excellent.

It’s easy to run, I feel I have the power and good mood. I feel like rushing to a bright future. Then I did not know that the future would be really bright because of the frozen crystalline lens. But first things first.

0–20 km

I’m running not too fast—six and a half minutes per kilometer. Approximately 9 km per hour. Strength and energy must be kept. There are six gels and 1.5 liters (50.7 fl oz) of warm sweet tea in my car. Should be enough. There is also a spare mask and two filters for regular replacement.

Well, it’s time to meet my “hippopotamuses”. First came Hypoxia – (oxygen starvation) – low oxygen content in the body.

I am familiar with this monster firsthand — my freediving and pranayama experience was very useful to me. I know a lot about breathing, blood oxygenation, the activity of the lungs and muscles. I ran up the stairs in a hypoxic mask, and in the morning, sitting in the toilet, I held my breath almost to faint. During the competitions I danced “samba” several times when I forced my body to stop breathing. You jump out of the water, you take a breath and … you start trembling: your hands, feet, and head shake, and you are absent. But actually this is not very funny. Without any supervisor around you, you can drown even in a shallow pool.

The freedivers’ hypoxic training is only suitable for those who have cast-iron will, because they teach their body to endure the suffocation of agony. Despite this, freediving is not harmful. On the contrary, it very much develops the lungs, the circulatory system, and teaches the body to use low doses of oxygen.

After two years of training, I am now able to hold my breath for 6.5 minutes, and the volume of my lungs can expand to as much as 7 liters (236.7 fl oz). As a global standard, it’s a modest result, but for an average person it’s a serious thing.

After half an hour of running, I felt that it was getting harder for me to breathe, and the muscles in my legs, lacking oxygen, started to get heavy. I exhaled with force and saw a jet of “smoke” burst from the top of my mask. Not from the mask, but from above. To onlookers I appeared as a dragon blowing smoke from his nostrils. In short, the mask was clogged with ice, so I raised my hand.

By raising hand we agreed to signal the need for help. The front car is waiting for me and now driving next to me. The door is opening and Andrey is popping out:

— Can I get you anything, sir?

— A mask, please.

— I’m afraid it’s too early. We planned to change it once an hour.

— Pardon, mistaken forecast!

And here I put on my mask, warm and breathable, but my legs do not recover completely. Lack of oxygen is felt. To recover, I have to stop filling my oxygen pockets. When practicing Pranayama, I breathe very rarely and deeply: less than one breath per minute, and the body is saturated with oxygen to the limit. So now I’m starting to breathe slowly. Long inspiration, long expiration. Long breath – long breath. Thus, the body absorbs oxygen better. And the legs slowly begin to revive. I take this strategy as a basis and continue to run.

Sanya shoots me from incredible angles, hardly bending his fingers to adjust the equipment in cold temperatures. Then he takes a look at the thermometer. Oh, it’s showing -60°C (-76°F). The goal is reached! I take out the Kestel portable weather station and on the run I fix the perceived temperature: temperature + wind + humidity. The device shows -67°C (-88.6°F).

Brrr, I never thought it’s possible to run at such temperature. Even on Mars, they say, it is warmer by daytime. The average temperature on Mars is about -40°C (-40°F). In summer, in the daytime half of the planet, the air warms up to 20°C (68°F), but during the winter night the temperature can go as low as -125°C (-193°F), and at the poles it can get as cold as be -170°C (-274°F).

Predawn hours are the coldest. It will continue to warm. Although it is unlikely that I will get warmer — a few degrees up at this temperature does not change the things.

And here comes the dawn. My face has long been icy, but I can support the pain. It was colder when the oncoming ice wind hit into the bare face. Now it hits the icicles, which make sort of ice shell for my face.

Now … in my mind I go all around my body, doing a running check-up:

✓ Face — cold, but what can I do?

✓ Head — all right

✓ Nose — cool

✓ Body — chilly, and it should be so, otherwise there will be a lot of sweat

✓ Elbows — warm

✓ Bottom — freezing, and it’s not okay

✓ Legs — comfortable

✓ Feet — warm, heat packs are doing their job

✓ Brain — running like clockwork, thinking positive

I realize that the systems are all right, therefore I seize the moment to enjoy what is happening around. After all, very soon I will have no time for snow-white trees, diamond dust hanging in the air with billions of ice-cakes, not even for the rising sun and sparkling snow.

I’m smiling like someone who is watching an enormous flaming meteorite that is grimly approaching the Earth, and in a few moments will turn it into a scorched desert. Unable to change anything, these last few minutes, people admire the sunset, trees and birds singing.

I tried to remember this false sense of paradise.

As very soon it will become hell.

20 km — 38 km

It’s been two hours since I took the start. Dawn is behind, the thermometer shows -58°C (-72.4°F). The have to change my mask every half hour, and each time the muscles get clogged up more and more. To be honest, I had a crazy idea to run 60 km, if I feel great. But after the twentieth kilometer, the ice-burning Yakut wind completely blew this stupid idea out of me.

Time to have a bite. I have a modest supply — five energy gels and a plastic bottle of warm and sweet tea. Usually I eat no more than three gels for a marathon, and I don’t drink sugary drinks at all. This time I decided to take with plenty to spare. As it turned out later, I should have taken even more … Here I raise my hand, the front car stops, and Andrey runs out of it, fetching me some gels and tea. I slow down to a walk and squeeze the gel into my mouth.

NEVER BEFORE have I eaten such delicious gels. They were so… warm and sweet — and that was exactly what my exhausted body longed for. Each feeding was for me like a trip to a restaurant — I counted every kilometer until the next portion of warm sweet nectar.

It was about then that the second “hippopotamus” appeared — her majesty Hypothermia, or excessive heat loss. And I knew this monster very well, too.

I’ve had several “cold” races under my belt: the icy ToughGuy — one of the most difficult endurance races in icy water; the Baikal Ice Marathon and the North Pole marathon; Otillo, where I had to swim in sneakers 10 km in 12-degree water and run 65 km along the rocks; the Arctic Swim in Teriberka Bay; climbing Mont Blanc and Elbrus.

Sometimes, in the cold, I was shaking, freezing, overcooling, legs cramping, fingers and nose freezing. Thank God, I stayed safe and sound. But not everyone is so lucky — let’s see what happens to a person who is not dressed for the weather, say, in wintertime here in Oymyakon.

Body temperature 36.6–35°С (97.88–95°F). A smart body will, first of all, try to protect itself by making a heat-insulating fur coat out of poor human materials — raising body hair. Then there come the goose bumps. But it protects us from cold just as fine as the fishing net protects fish from water.

35–33°С. The body constricts the vessels located on body surface, leaving most of the blood (heat) in the central part of the body. No time to stock the fat, if only it were enough for the heart and brain. As for the periphery — hands, feet and nose, let them freeze, you can do very well without them. The person’s nose goes red, hands and feet begin to freeze, and the mood darkens.

33–31°С. The body is cold and takes all for serious, so it includes another effective protective mechanism: the muscles begin to contract quickly and uncontrollably, while warming up and giving warmth to the whole body. That’s right, the teeth rattle in the cold because of this. True, this is a rather expensive way of warming up, since the muscles begin to consume a huge amount of energy. Breathing quickens, consciousness begins to get confused, vision deteriorates, coordination of movements is disturbed, arms barely obey any longer.

31–28°С. The body panics: “Commander, we are dying!” All defense mechanisms work to the limit, but the body temperature continues to go down. There is very little energy left, not even enough for the brain: hallucinations appear, the ability to see and hear disappears. In a desperate attempt to warm up the frozen hands and feet, the body decides: “Let’s go out with a bang! Let’s go the whole hog!” And expands the peripheral vessels. Warm blood rushes to hands and legs, and the person gets … hot. Therefore, freezing people often undress and, in consequence, die faster.

28–17°С. After the final breakthrough, the body understands that cake is dough: heart rate goes lower than normal, the person tends to sleep and cannot sensibly assess the situation, along with weak breathing and incoherent speech. There is no more pain or cold. Hoping for a miracle, the body switches to emergency mode and disconnects: the person falls asleep, and then falls into coma. Heart rhythm is disturbed, pulmonary edema develops, and then the heart stops. Oxygen starvation makes the brain die. In short, this stage is the shortest and the most dramatic.

And here come the earliest signs — cold leaks from everywhere. My back and my bottom are the next to freeze, the first is my face though. Elbows, thank God, are warm (thanks to Andrey for the pockets, in which I put heat packs). But the cold starts to pass through two pairs of gloves — I probably dressed too warm and was sweating, and now the cold is sneaking through my moisture to my skin. What matters now is how fast I will cool down and whether I will have time to finish the race before the cold stops me.

— Dimon, but why didn’t you get into the car to warm up? —some wise readers would ask. — Warm yourself, then go on running, that’s it.

A very opportunistic way out, indeed. Possibly for someone, not for me. I set myself the task to run a distance without rest, warming up, sleeping, changing clothes, hot food and baths. Without doctors and without rescuers. Otherwise it would be some kind of game with yourself. After all, resting like that, you can run 1,000 kilometers, getting enough sleep in the car at night and moving two to three hours a day. Therefore, I ran without heating and rest, only slowing down to a walk a couple of times to drink tea and change the mask.

When there were 30 km left behind, I decided that I would fight for 50 km (our optimistic plan). In general, we had three plans, depending on health condition, weather, force majeure, vehicle breakdown, masks, equipment and other:

1. 1. “Anything” — 38 km (Tomtor – Oymyakon)

2. “Classics of the genre” — marathon distance, 42.2 km

3. “Gloves-off” — ultramarathon, 50 km

After appreciating my adequacy and appearance, the guys did not approve of my choice, therefore they insistently suggested me to stop as soon as I reached the marathon. After a short debate, they realized that they were wasting their time, sighed and poured me some more tea.

I’m running. Trying to escape from the cold, deconcentrating. Here and now it is not difficult: monotonous steps, a white road, diamond dust hangs in the air — this is how meteorologists call frozen mist, consisting not of water droplets, but of tiny ice particles. Amazing spectacle, when the sparkling mist spreads along the ground and shimmers in the rays of the sun hanging over the horizon.

There is Oymyakon, 38 km left behind. The minimal plan is complete, I can mentally exhale and prepare for the next landmark — 42.2 km. In difficult races, I always try to break the distance into pieces and think only about intermediate finishes. As in business, long projects need to be split up into stages — it is easier to understand where the project goes and when it will be completed. I have two finishes left. The next one is in 5 km — playgame. We’ll hold up.

Dogs are happily greeting me. Heck yes! People don’t run too often in these neighborhoods. And so they accompany me as I’m entering the village.

The stela with a thermometer stands there in the middle. I take a lap around it and with the corner of an eye glimpse the temperature of -55°С (-67°F). It’s getting warm. But it feels like there’s no difference. Although on the other hand, at home I hardly feel a warming from -10°С (14°F) to -9°С (15.8°F).

People meet me, waving their hands. Suddenly, I am overtaken by a “Buran” snowmobile with a photographer on board. After the race, I learned that it was Chyskhaan, who in combination with the fabulous post of Yakut Santa Claus works as a photographer. Taking pictures of me far and wide, he sped off, leaving me alone with the road.

42.2 km— the marathon

It’s getting hard to run. The speed drops, the field of view narrows, it becomes very cold, and the legs feel as if they were stuffed with cotton. These are the first signs of the third “hippopotamus” — Hypoglecemia, or simply said low blood glucose or low blood sugar.

It’s an old friend of mine, I know everything about it. We have met many times. Descending Mt. Elbrus, at the Ironman race, at 85 km of Comrades, in the middle of Gibraltar, at New York marathon, at the Oceanman competition in Mexico and in the Sahara desert after 10 hours of running. I know it in-and-out. But I prefer not to meet her.

Usually, it is easier to fight it off — you need to stop and eat something sweet to quickly raise your blood sugar levels. And it is good when you have where to sit and what to eat. It happened to me in different ways. Today the situation is a little unusual — my body spends energy faster than I receive it. And all because of the first two “hippopotamuses” ? In theory, I need to stop and eat a sweet hot meal, but it seems to me that it’s unsportsmanlike under such conditions, and so I run on.

Sasha observes me with the thermal camera to see where the heat leaks were, to fix the equipment for the future.

And we’re done with the marathon — 42.2 km! Actually, I can fall into a snowdrift — already a hero. But as long as I have forces, I shall move. Cold, hard to breathe and absolutely no strength. But I’m running … The guys are looking at me with anxiety, checking if I’m really ok? I’m OK! Of course, friends, always the way!

My hands were insensible from cold, but it did not matter then —my brain began to turn off the useless pain receptors. I just began to slowly turn into a block of ice. At the 45th kilometer I raise my hand. The car stops, and I gladly do the same.

— I-have — to-chan-ge my-gloves, — I could only utter by syllables.

It took Andrey quite a while to take the frozen gloves off my hands and put on a new warm pair. In the car, the guys turned them inside out — there was frost inside the gloves. Still, water is the main enemy of thermal insulation. I greedily drink warm tea and Andrey covers my face with the last bits of polar ointment.

— The fi-nish is in 5-km. Drive-the-re, wait for me, — I utter slowly.

— Are you ok? You don’t look well, — Sanya said.

— A-por-ppro-pre-pri-ate, — I mumble in answer. — What-am-I sup-posed to look-like?

I put on a new mask and, sighing with relief (if it can be called relief), I trotted on and the guys went ahead.

Finish

The last 5 km were so hard for me. Kilometers stretched, turning first into miles, then into triple miles. The speed dropped to a Jewish pace — 7:40 per km. The movements slowed down, the vision became blurry and even my thoughts froze. In my head there was some frozen mixture of images: Chyskhaan, drinking warm tea out of a crumpled plastic bottle, someone shouting “Come on, come on!”, Vica is cooking a rabbit, cartoon death, diamond dust …

I’m shaking my head, coming to my senses, running. The watch is showing 47 km, there is little left. In order not to fall into the subconscious, I raise my hand. No car. Damn, I sent them to the finish… All right, I’ll flounder my way— 3 km left, not 50.

The spots of discomfort that have been bothering me for the past few hours have dissolved into a general buzz of sensations of detachment and loneliness. There was no more pain, just a desire to lie down in a warm place, curl up and fall asleep. I clearly understand that I was left alone with the road. There are no cars, no escorts, no people — all disappeared. As if the meteorite DID reach the Earth… I was all alone in an icy desert. A thought came to my mind that when a soul leaves the body, the person feels just the same absolute solitude — there is only you and your path.

Peripheral vision has been turned off by the brain, as a meaningless energy expenditure, and tunnel vision is cloudy, as if looking at the road through a jelly. In fact, I saw a spot of white background, on which red sneakers slowly flashed. I believe that at such moments when the consciousness is so tired that it hands over control to the subconscious, we can learn a lot about ourselves. The main thing is being able to decode these images, or at least remember them. Believer:

Pain! You made me a, you made me a believer, believer…

Pain. I realized long ago that this is the fastest way to the top, but the hardest though. Overcoming it, you cease to be afraid of it and become more confident in yourself, and unlimited self-belief gives unlimited possibilities.

Under the ringing of icicles on my eyebrows and the measured snow creaking of my steps, I “ran” another two kilometers. Having hardly seen the figure 49.2 on the watch, I cheered up. But where is the finish line? Instead of the finishing tape, I saw a Hill. Why capital letter? Because I felt like conquering Everest — it was so difficult for me. If they gave me an ice axe in my hand, they would say I looked like Percival Hillary.

I look at the approaching peak through shaking icicles, because from there I will see the guys for sure. Without breaking in pace, I storm the hill!

And of course the guys are not there. I look at my watch blankly — 50.1 km. In my mind, I’m making use of all my rich vocabulary to wish them well, love and harmony with the world … After a painful death. In any case, it won’t be long now, and, clenching my teeth, I rush (what a ridiculous word in my case) … Forward!

Here come the guys! Hundred meters. Well, now I need to get the flag, lift it over my head and finish. I stopped the training on my watch, deftly snatched the flag, quickly straightened it and ran to the finish line. You can see for yourself how deft and fast it really was:

And here I cross the improvised finish line — the towing rope of the bukhanka. Total surrealism. I fall to my knees. That’s all. I did it. I am trying to sum up something important to say in front of the camera, but in my head thoughts are so thick like vodka in the cold. I mumble something unintelligible about outer space, rarefied air and unearthly cold. Gagarin, damn it. Although this race really looks like a spacewalk for me. And to visit space has been a childhood dream of mine.

I send my greetings to Eva — I did what I promised; I fought Ulu Toyon, but it turns out that no one is filming me. Instead, they push me into the car and undress me.

Naturally, there is a layer of ice under my jacket, white frost on my face, freezing mist in my gloves. I was looking like Santa Claus getting back home after a day at work. Unnaturally dwelling on words, I thank the guys for not letting me shrivel up somewhere on my way.

Hormones begin their restoration work to protect the brain from stress, and I begin to smile silly. People are bustling around me, the camera clicks. Someone laughs, clothes, clothes, tea, more clothes, congratulations — everything merges into a slow-motion video. Like watching on a frozen LCD screen.

And I smile at the thought alone — “it’s all over, you need not run”. Although the picture doesn’t show this, you got to believe me —my inner smile was wider than Gibraltar. By the way, such a race is a splendid occasion to make the worst photo in your life:

After

In half an hour we were at home — I climbed under the covers and periodically looked out. While we were driving, I gave little importance to the fact that everything was blurry around me. I thought ointment got into my eyes. But at home I rubbed my eyes and oops … Nothing has changed. I was looking at the world as if through a pebbled glass. I got tensed in earnest. Before we left, someone had warned me that people who had undergone surgery on the cornea should not be exposed to cold for a long time. I ignored that and now I have lost my sight.

A small panic began. So small, with a slight increase in pressure and pulse and trembling hands, trying to wipe the eyes, then look for salvation on the Internet. To onlookers it probably seemed so cute. But I was not in a playful mood…

Vanya entered the room and witnessing my panic hurried to comfort me:

— Your crystalline lens has frozen and dimmed. You’ll be okay in a couple of hours. This happens when you ride the “Buran” for a long while.

There came a hope that I would be able to look at the world with my own eyes and would not need to develop a third eye.

I sighed with relief and decided to wait. At this time, Andrey came running from the pharmacy and dripped some drops into my eyes. An hour later I was already looking at the world through a transparent and clean lens, like a Yakut diamond. I breathed a sigh of relief. Somebody keeps me safe and secure…Vica, just spit it out, are you involved?

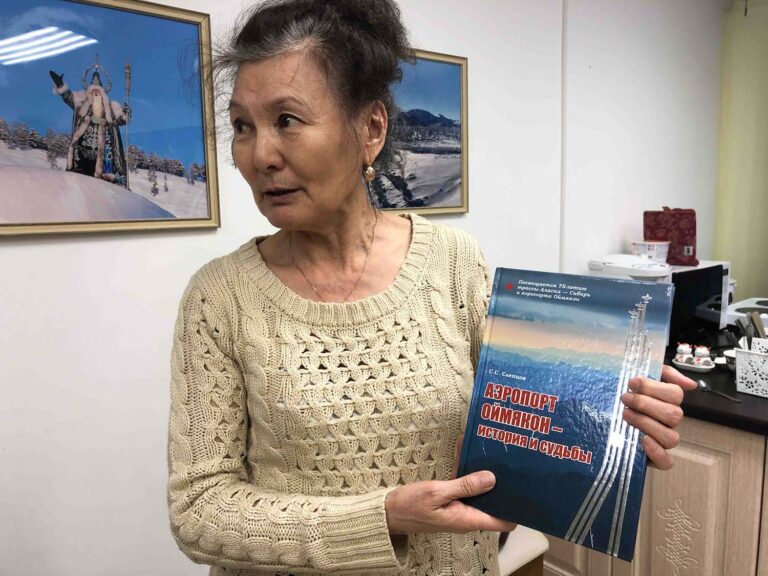

What followed next was a lavish feast —representatives of the local administration, employees of the local lore museum, and neighbors came to congratulate us. They brought us books and souvenirs as gifts, they even set the table for us.

Vanya brought us a delicious cake, which we kept eating all the night. Perhaps it was not quite sportsmanlike and useful for health, but very sincere, fun and heartily!

Vanya admitted that he did not believe in me, but now he began to respect him and, cutting off a claw from the bear’s skin, handed it to me saying:

— You are a stout-hearted man. I respect you.

For me, this is a very important gift — getting recognition from the Yakut hunter, who constantly risks his life. All my medals are not worth this claw alone.

In parallel with the party, the guys sent photos and videos about the race to the mainland. At four in the morning we went to bed. And in a few hours we woke up famous.

Unspoiled by fame

We guessed that things would evolve into a cause celebre, but we had not realized to what extent. On the first day I became the hero of Yakutia. I was congratulated by oncoming people. We were taken to the local sports school, where local boys wanted to take pictures with us, we were given certificates that we visited the “Pole of Cold”. The phone began to overheat from plenty of messages.

On the second day I became famous for all of Russia. My phone has already overheated from messages and calls from television and the press. The guys and I looked at each other, perplexed and not fully realizing what had happened. Then Eva’s mother called and thanked us heartily for what we did for her family.

The news about our race has become the most readable on Yandex news. I was invited to TV shows. My picture was displayed in the subway, in newspapers, on TV and on the Internet. Hundreds of websites published the news, television channels shot dozens of reports. The President of the Republic of Moldova noted that it was an honor for our country and also promised to help little Eva. Evan Zhirinovsky, in his characteristic style, commented on the record race at the “Pole of Cold”, wondering what has got into Moldovans that they won’t sit still and keep warm.

On the third day, the whole world learned about the Moldovan who did the “impossible”. Friends from abroad started calling — they talked about us on world-class television channels. Euronews, Reuters, Dailymail posted reports. Hundreds of videos on social networks told about the charity run in the cosmic cold and about raising funds for little Eva.

In a word, I grew more and more famous around the world. But is it deserved? — this is the question I then asked myself. After all, I did not discover a new continent, did not invent a cure for cancer, did not run the fastest marathon in the world, because I’m not even a professional athlete. And I understand perfectly well that what I did is within the power of many runners. And I am sure that next year the hot-brains will come and run further and faster than me. Therefore, I am convinced that fame went too loud and bombastic.

And here we are, flying back home. Suddenly, on the speakerphone, the commander of the crew of AirMoldova congratulated me. They gave us a beautiful plane as a gift and poured us champagne. It was unexpected and sooo nice.

And what was awaiting us at the airport —I have no words to describe that. It’s better to take a look. You moved my heart, devil take you. Thanks for the surprise!

And if we talk about the results of the Unfrozen charity, then the result exceeded our expectations. People want to help little Eva fight for a happy childhood. The action was joined by ordinary citizens, legal entities, and even the President of Moldova, who donated a considerable amount for the little girl.

With joint efforts, we have by now collected more than 12,000 euros for Eva, some of which have already been transferred for rehabilitation in St. Petersburg, where they went the other day. Little Eva deserves not just a fairy tale, but a happy-end fairy tale. And so that she never gave up, the fairy-tale character of Mitro handed her a pendant, which he took away from Ulu Toyon himself — the evil Yakut spirit who had bound the little girl with the spell of cold …

…Well, I remained unspoiled by fortune and affluence. Now it’s time to try remain unspoiled by fame. As they say, this is the most difficult test. More difficult than running an ultramarathon at -60°C (-76°F).

Finally, I want to thank my family — my kids and Viculya for trusting me and letting me go. Only she knows what she has gone through. Friends who have lived with me side by side probably the hardest two weeks of their lives on the edge of the world — Andrey Matcovschi and Sanya Berdichevsky. All our new friends from Oymyakon — Vanya, Katyusha, Gennady, Afanasiy, and all our old friends from Chisinau, who worried and waited for us at home. All who shared their warmth and helped Eva, and, of course, all those who kept their fingers crossed for us and who believed in our insane adventure.

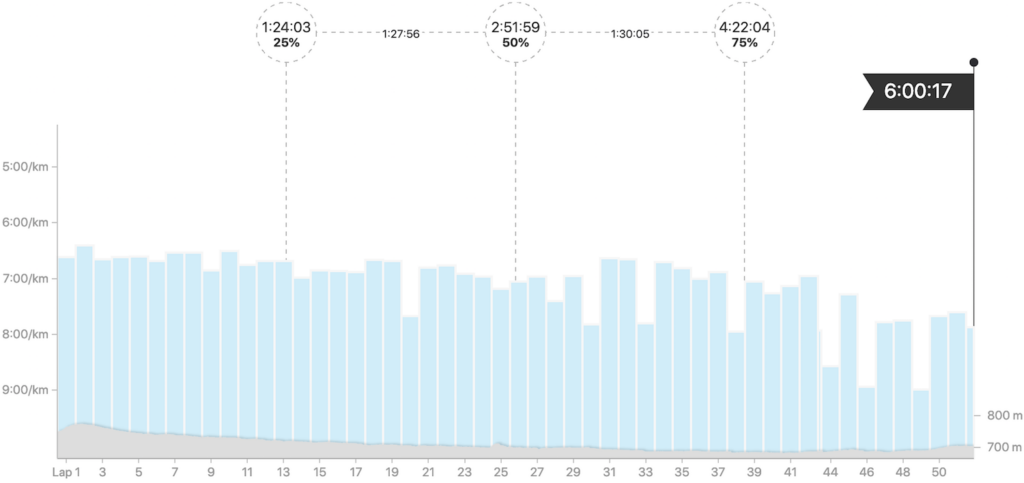

Figures, tracks, certificates and other stuff:

And here is what was recorded by the rear camera in bukhanka. I sped up the video 100 times. But if you want to watch the complete six-hour version, it is available here.

Garmin gps-track with pulse, cadence and other trifle ?

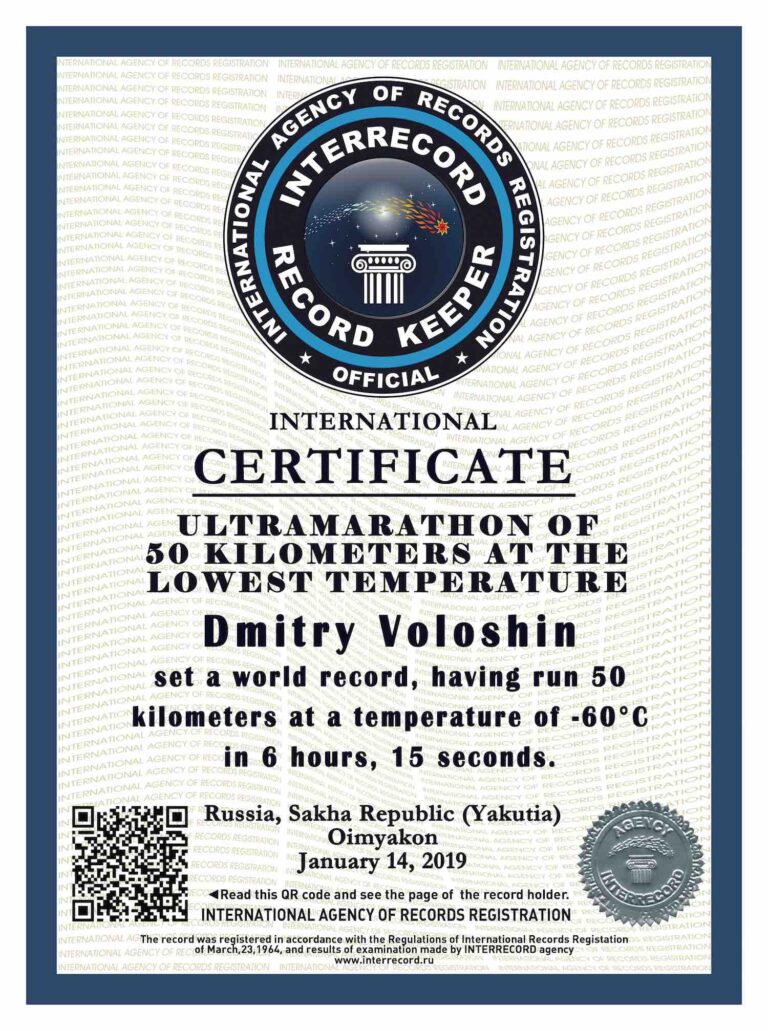

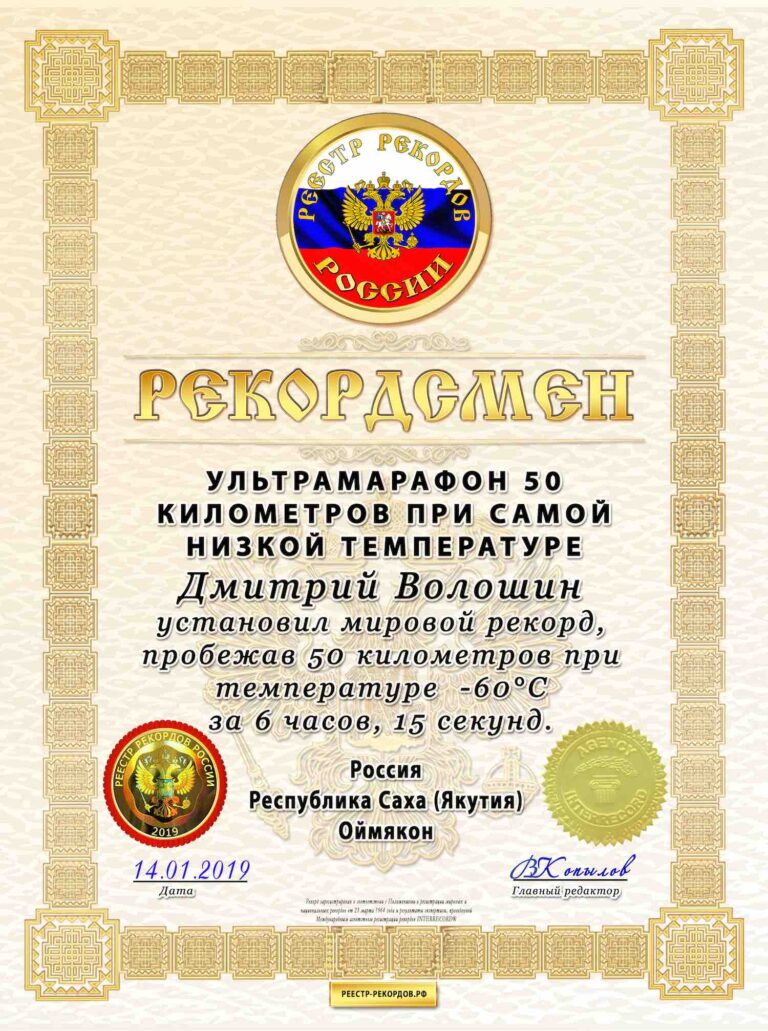

Based on the materials and documents provided, two registrars— the International Agency Inter Rekord® and the Register of Records of Russia®, officially formalized the record.

Mission accomplished — covered the distance, came back, hugged everyone, gave some interviews, wrote a post and lay down on the sofa. On the very sofa where I rested a couple of years ago, when the idea came to my mind:

Why not take a run in the coldest place on earth?