A hero is the most important piece in the cinematic mechanism. After all, he or she is in constant motion and not just advancing the plot, but creating it. Yes, it’s true – heroes are those who create the plot, not the script writers 🙂 That’s why the main character in our cartoon had to be active, bright and memorable.

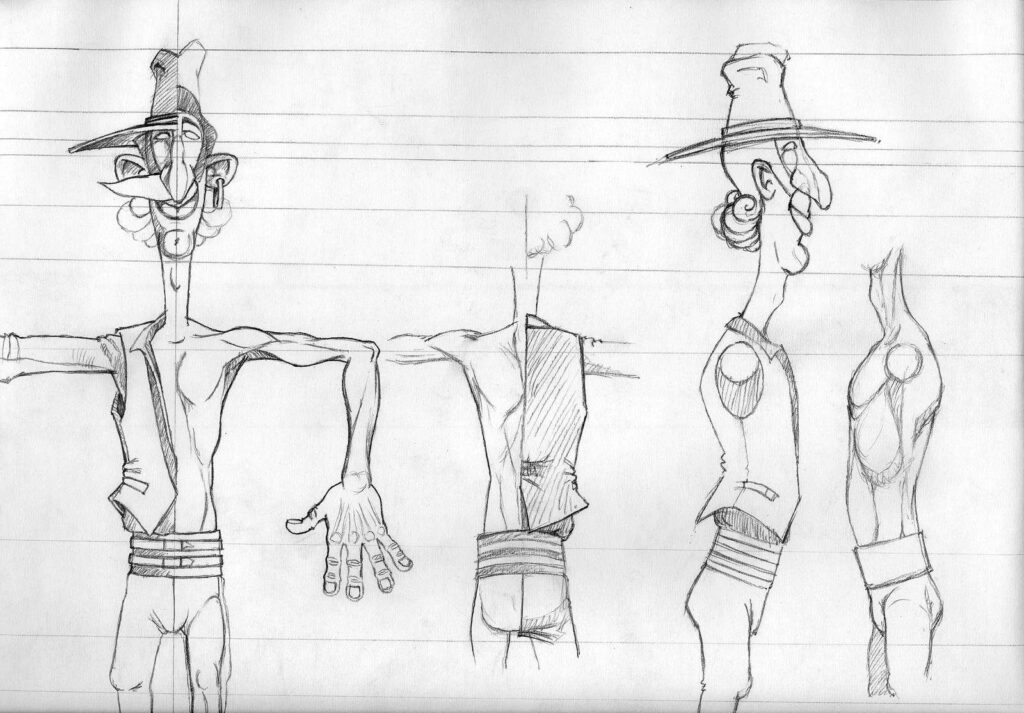

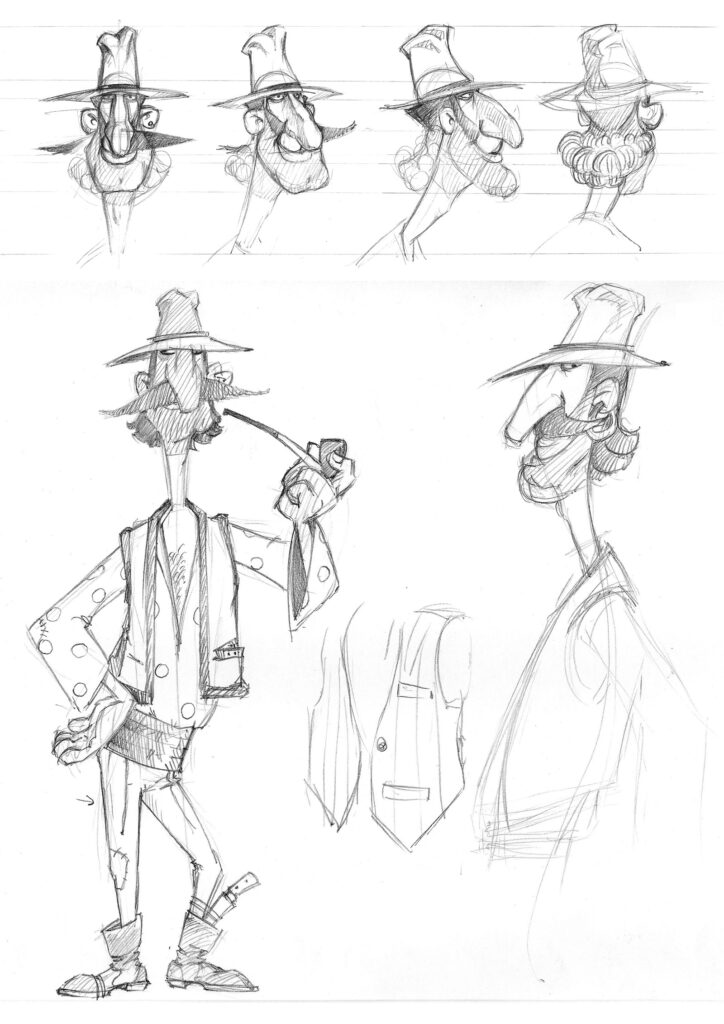

We basically figured out what he was going to do, but his appearance turned out to be a prolonged battle between the director and the production designer.

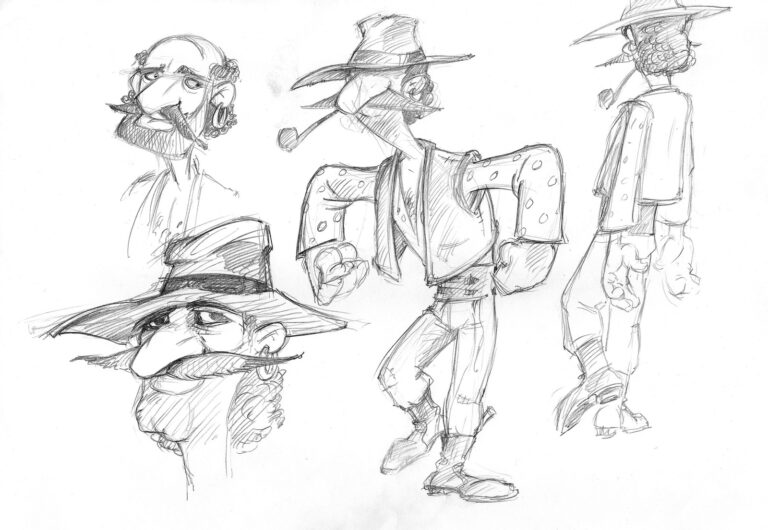

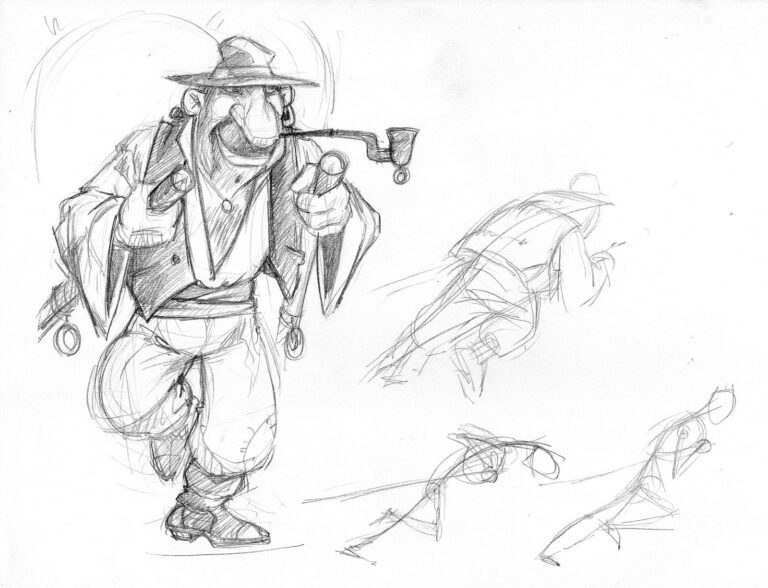

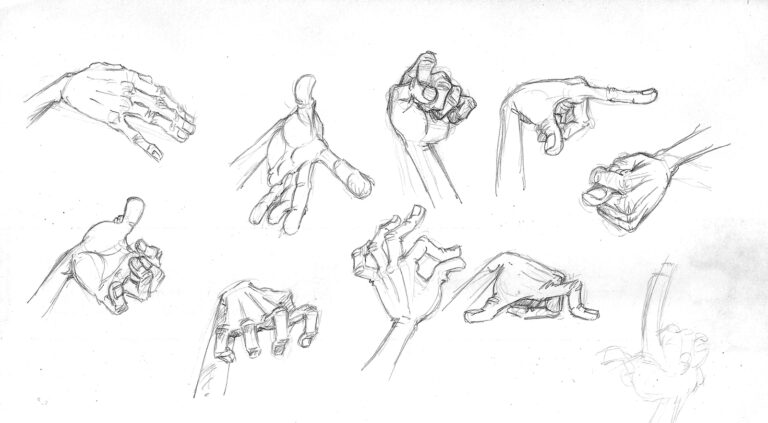

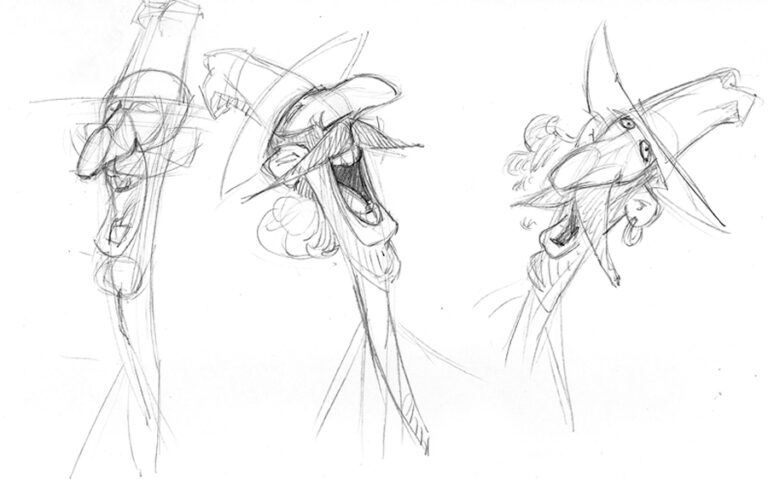

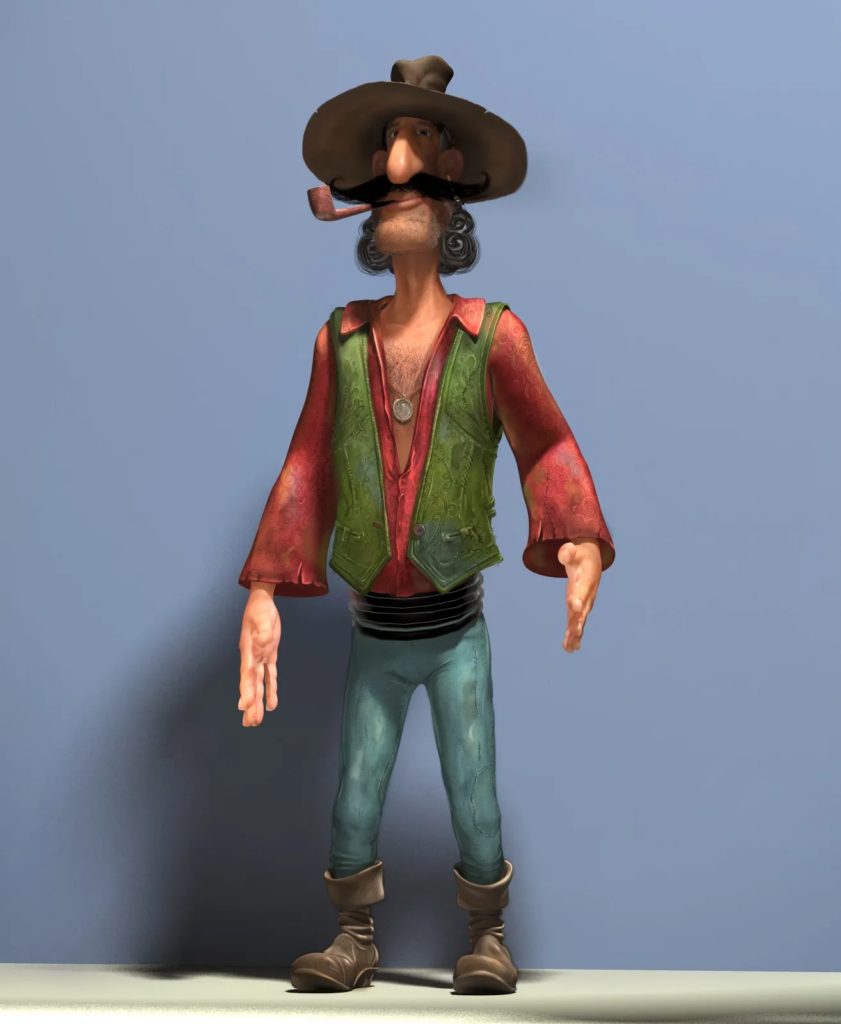

Our brave gypsy’s name is Gojo. And this name translates as “handsome”. And, surprisingly, this name fully characterizes the hero’s actions. Gojo wears a bouffant mustache and an earring. He smokes a pipe with Turkish tobacco. In his vest pocket he carries cards, a knife, a ladder, a spare wheel for the cart, and much more. He is cunning, manly, a little lazy, but assertive when necessary. Proud, stately, agile, cheerful and absolutely cheerful. In short, all women’s fantasy.

Pencil sketches were flying in different directions, erasers were whistling in the air, like real bullets. Serdar, our character designer, swung his pencil like a scimitar. I shouted:

– No, that’s not it; he lacks determination and freedom!

– Shall I give him some broken shackles? – Serdar resented.

And when the confrontation reached its peak, an image emerged that was a compromise of prowess, Indiana Jones and true gypsy character.

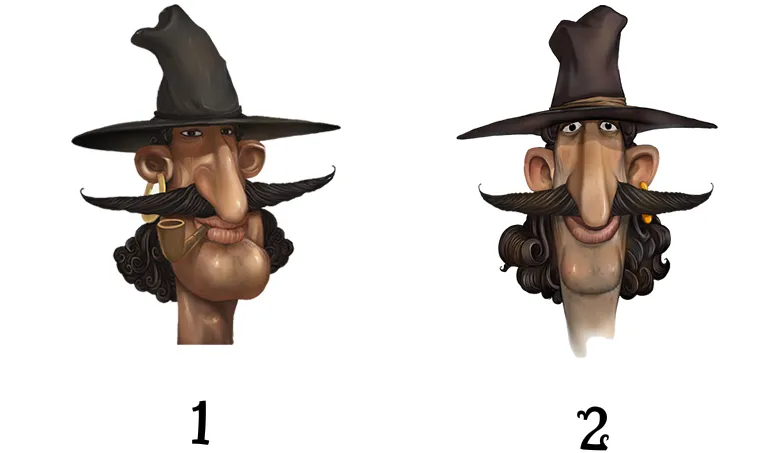

After the sketch is approved, the character ends up on the artist’s desk. The artist paints the character in the graphics editor, adds details, and brings the final image to a state of “so lifelike, wow!”.

This final image is signed by the picky director and production designer. That’s it, from that point on, these images become the benchmark.

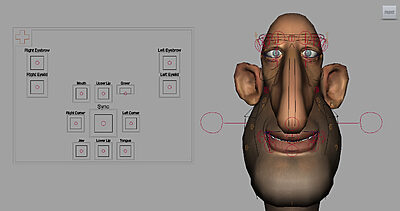

It took a long time to figure out which character traits were most important to convey in the appearance. Also, animation imposes certain restrictions on the character. Indispensable attributes of the character are permissible and impermissible responses – a list of rules which must be followed by the animator, so that the character would preserve his character in any of the film’s plans. For example, our Gypsy was strongly advised not to slouch.

Some more in different poses and angles in color:

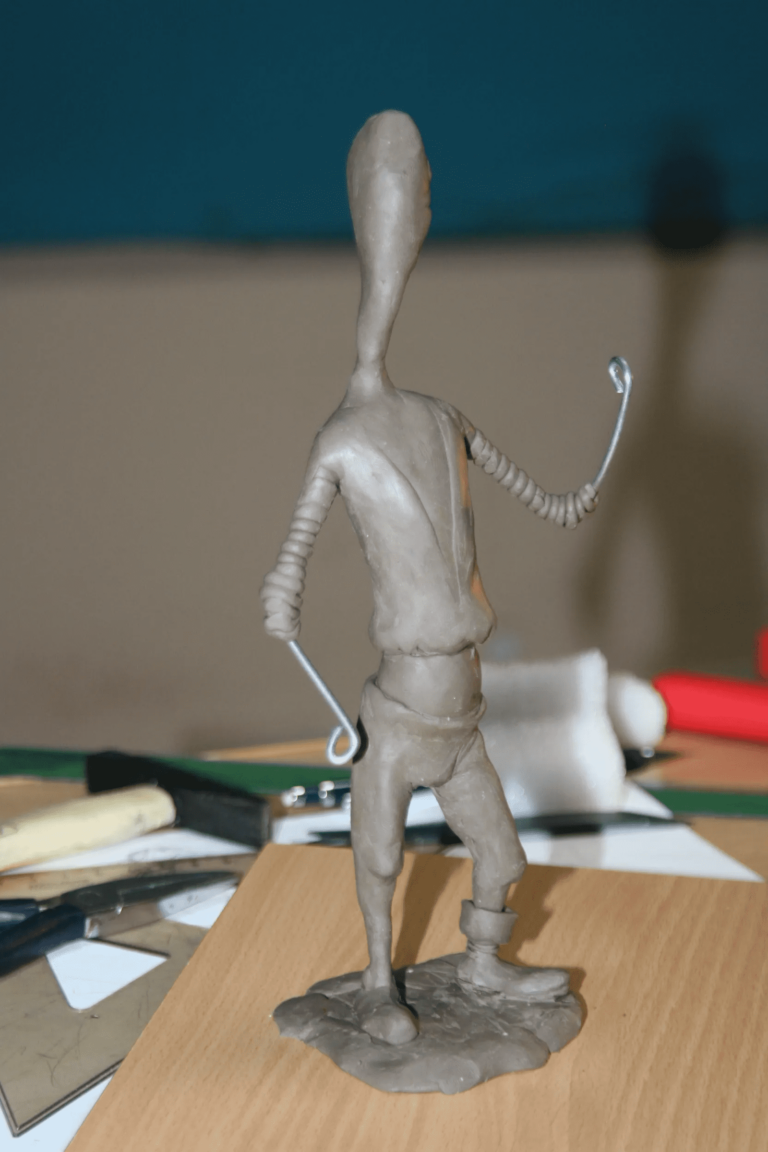

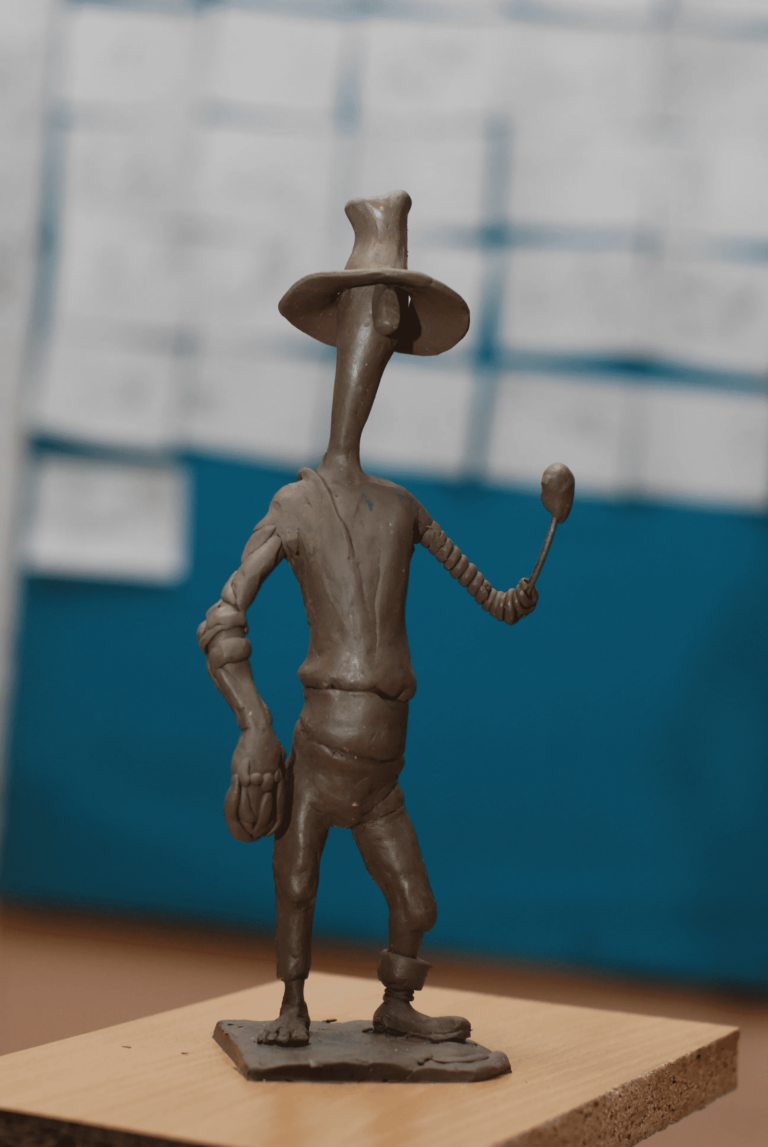

The plasticine model

In 3D cartoons, you can’t do without plasticine. Or rather, you can’t do without 3D models of the characters, which are made on the basis of sculptures. We decided not to break with tradition. We bought some special plasticine, clay and all the necessary tools, and gave them to our sculptor. There was something biblical and sacred about it.

Like God, the sculptor needed a lot of experience and an amazing ability to see and convey everything in dimension. He was inspired by our sketches and in a week, he showed us Gojo in all his glory.

Quite a complex stage of development, requiring experience and volumetric vision. In low-budget works, it is most often skipped due to the lack of specialists. We decided to follow all the rules, so we spent a week making a model of the main character out of special plasticine.

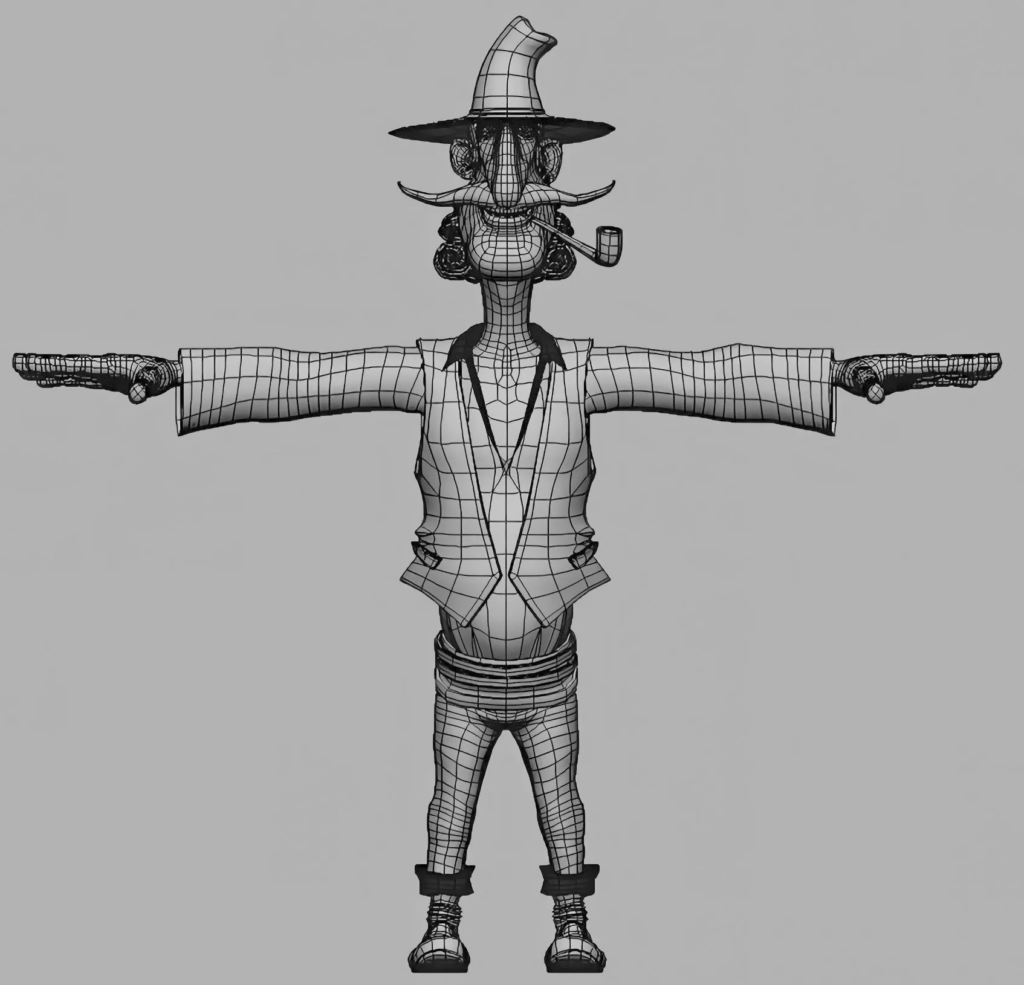

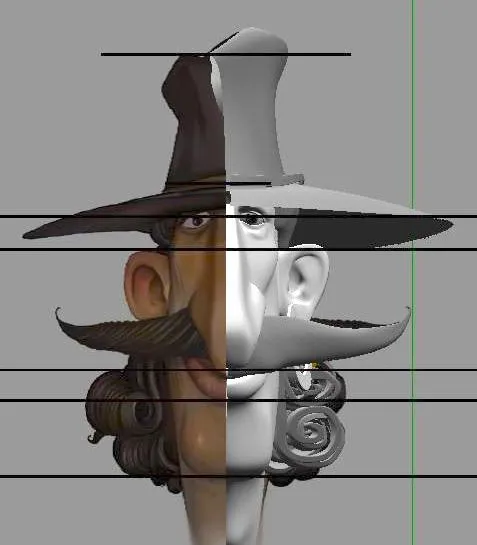

From Plasticine to Digital

Once the character is approved on paper and the plasticine model is ready, it’s time for 3D modeling. To simplify things as much as possible, this is how it is: we take a clear picture of the character, where it is shown in a neutral pose from the front and sides.

Next, we enter it into a special program and start filling it with small polygons.

The more polygons, the better. In a nutshell, the modeler’s work resembles chasing, only there is much less noise from the work 🙂

Here is a video:

Textures and coloring

Following the modeling, the next step is unwrapping and texturing the character. In other words, coloring.

When the model is ready, we need to put the texture of the character on it. Unlike people who have skin from birth, characters have their skin and clothes specially made. It’s like a gloved hand: the model hand on the inside and the skin texture on the outside.

This is not yet the final picture – animation, rendering and processing are yet to come.