Quite recently I found out that in Moldova there are ruins of one of the largest bathhouses dating back to the times of the Golden Horde. My friend Sergius Ciocanu, architect, restorer and archaeologist, told me about it. So I decided to dig deeper and we made a trip to Old Orhei.

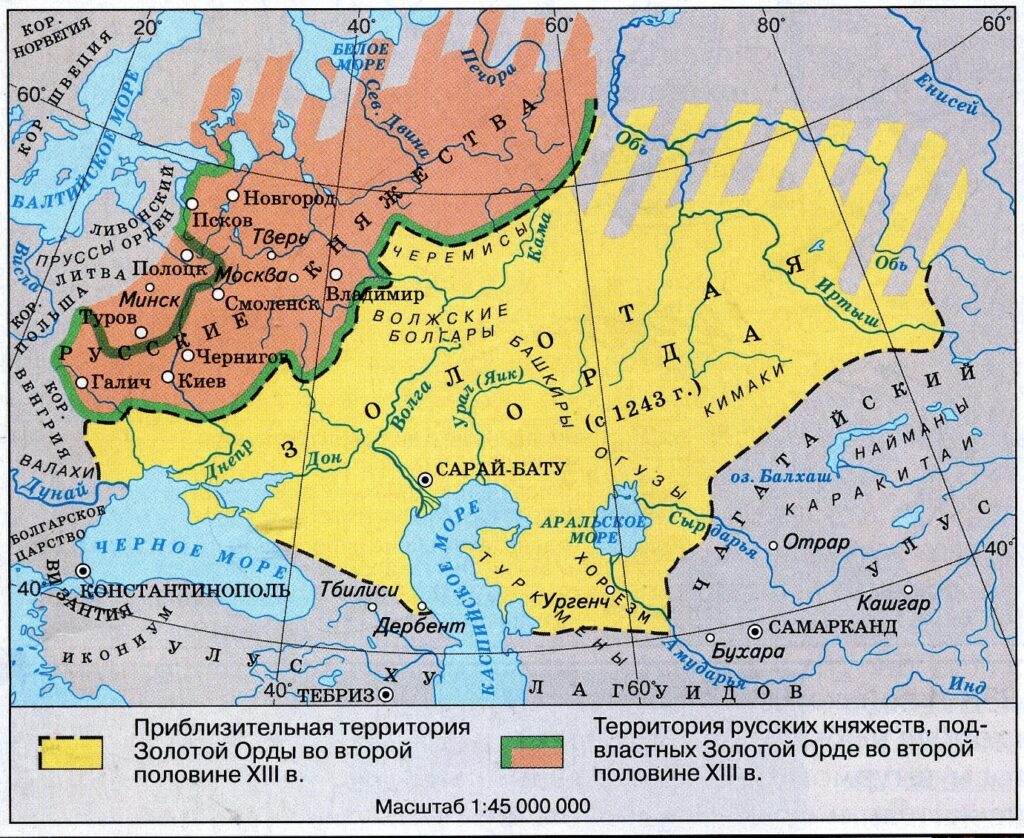

So, 700 years ago, when a part of Moldova was under the Golden Horde rule, the Tatar-Mongols founded a town in the territory of modern Trebujeni and named it Shehr al-Jedid (New Town).

Experienced craftsmen were brought here to build many public buildings, two hotels, a mosque, a stone fortress and public bathhouses.

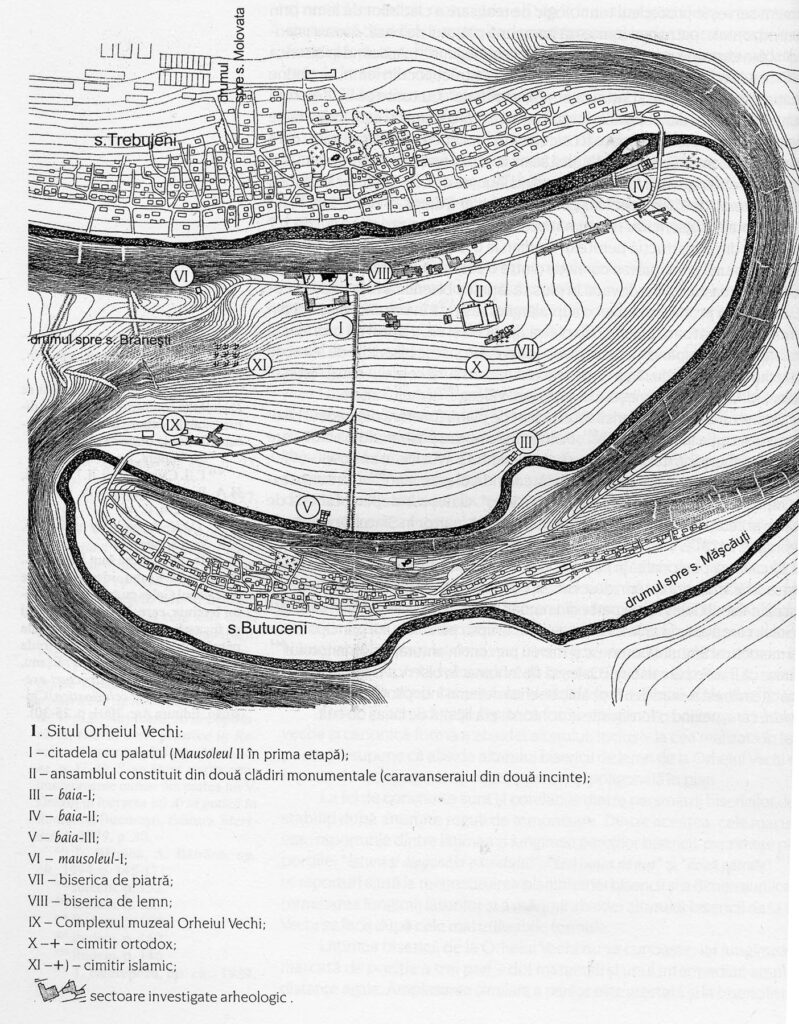

In 1948-1960, archeologists found the ruins of three buildings on the bank of River Raut in the area of Old Orhei. As it turned out, these were remnants dating from the Golden Horde period.

Bathhouses location (according to the scheme of the complex from Tamara Nesterov’s book “Situl Orheiul Vechi”, 2003).

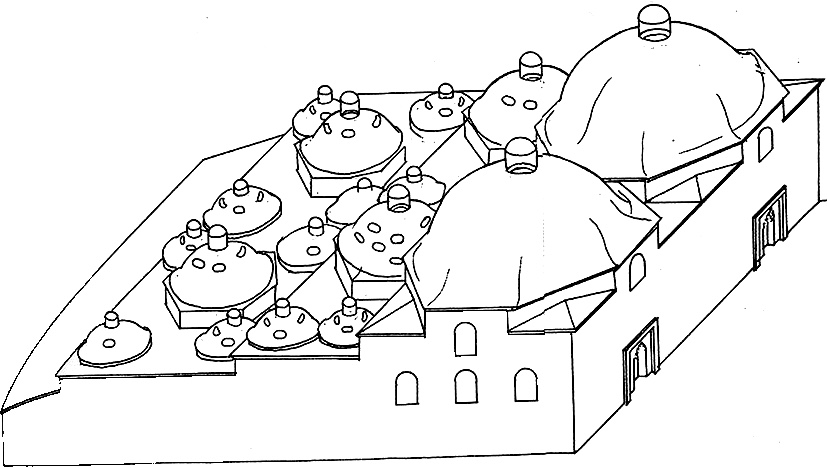

Bathhouse number II or Turkish bath is the largest of the three city baths discovered during archaeological excavations. The local tradition preserved its purpose as a bath, which is recorded in a document dated 1574 under the name of “feredeu” ( from Hungarian “fürdő” translating as “bath”).

Public bathhouses in the towns of the Golden Horde

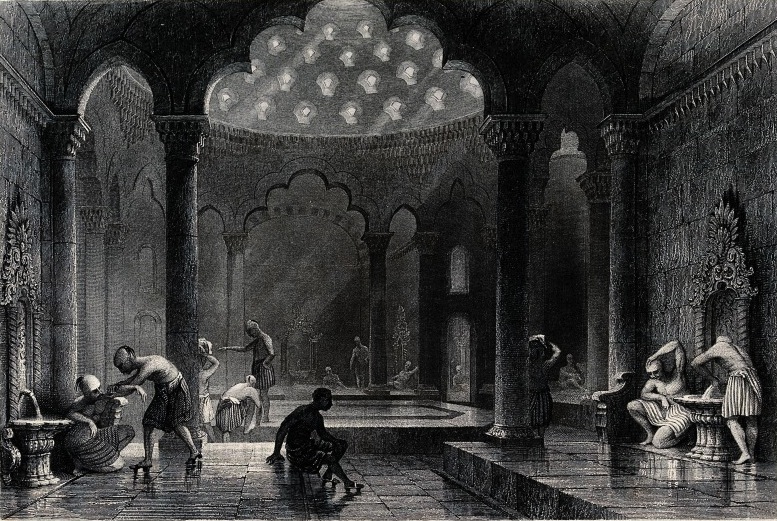

Public bathhouses in the towns of the Golden Horde occupied a special place in community life. The popularity of public baths was also due to the fact that they became a kind of “clubs” where visitors spent a lot of time.

Today we could call them ” a kind of “spa”, where people not only bathed, but also rubbed themselves with incense, special ointments, had small talk, were treated to sweets, etc. Public bathhouses were popular among all segments of the urban population, with cross-shaped public baths built for the wealthy, and more simple designs for the common people.

With the spread of Islam, the rites of which prescribed the compulsory ritual ablutions, public baths, known in Arabic as hammams, became an indispensable attribute of any eastern town.

In the oriental world the baths also played an important role in the lives of women, for whom visiting this establishment was one of the few entertainments. Women’s and men’s halves of the public baths were strictly separated.

In the Middle Ages, bathhouses also performed the functions of medical institutions.

The construction of a bathhouse

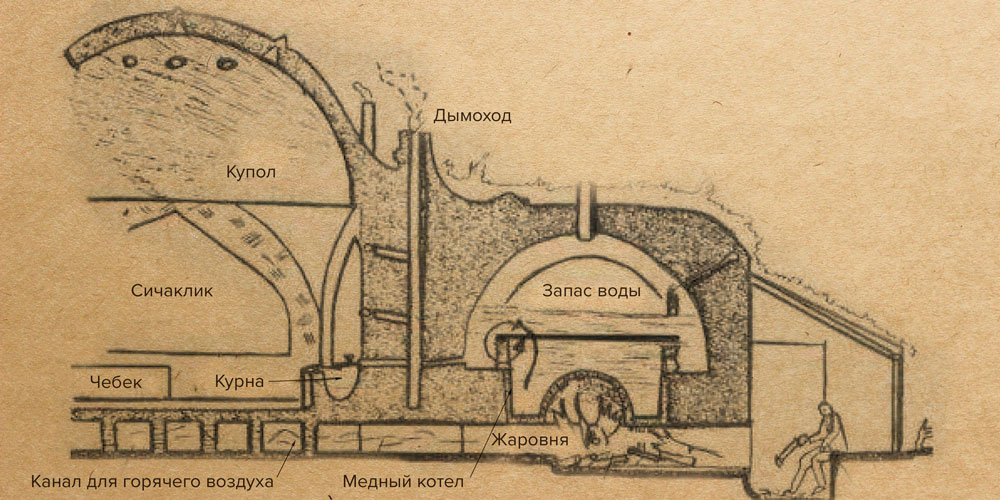

Oriental bathhouses are often compared to ancient thermae. The reason for this is the same structure of the heating system, in which the hot air coming from the furnace of the bath heats the entire floor surface.

Nonetheless, there were serious differences, one of which was the general layout of the building. It reflected the Oriental “ideology” of the bathing process, in which the most important element was massage, leading to complete relaxation of the body.

The Roman and later Byzantine thermae consisted of an enfilade of rooms with gradually increasing temperature, and the bathing ended in a pool with cold water.

While hammams in different countries of the Orient are somewhat different in layout and composition of rooms, their indispensable feature is the presence of a central hall representing the compositional center of the building.

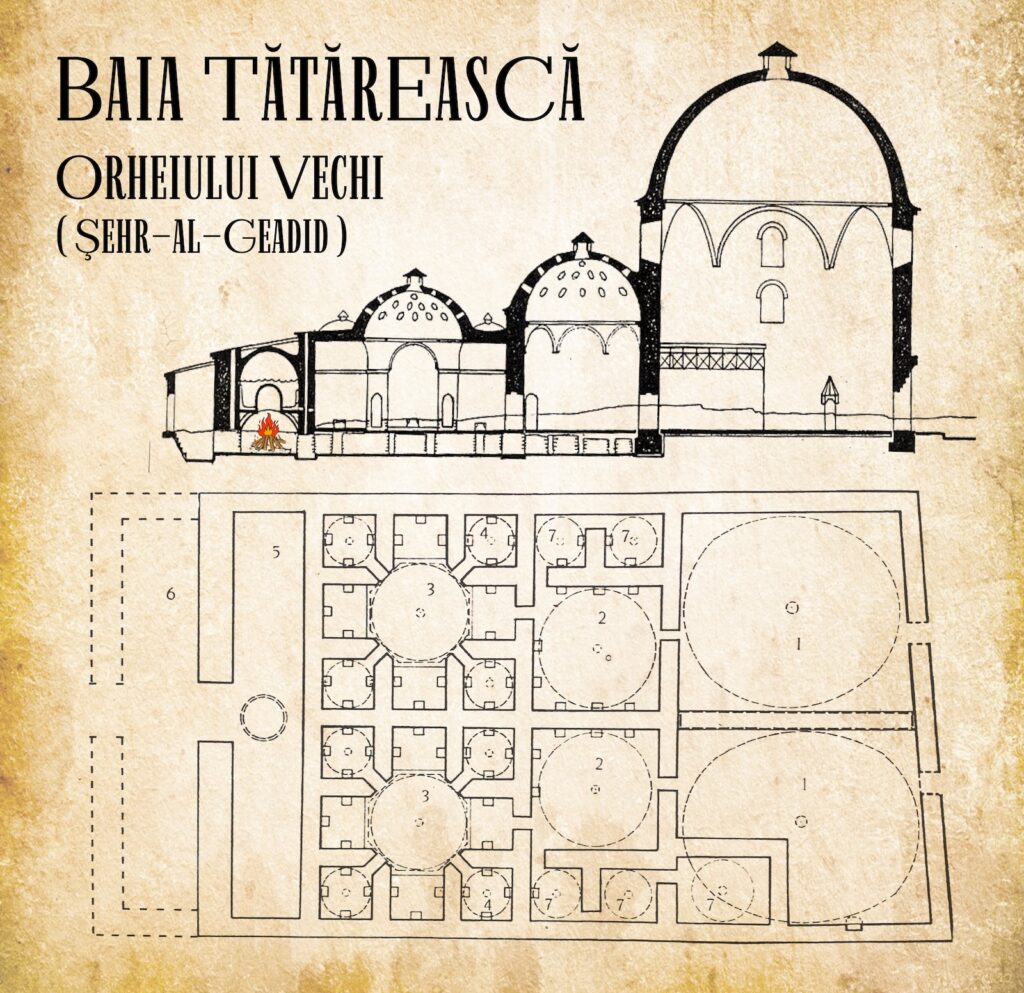

This typical hammam includes 6 main and 23 additional rooms, similar to their Roman equivalents:

1. Soukluk (Roman vestarium), also called kamekan or soyunmalik, serves as a dressing room and restroom. There you can leave your clothes, relax after the steam room, have a refreshing drink or sleep.

2. The warm room iliklik (Roman tepidarium) is an intermediate room between the cold and hot parts of the bath. Here visitors adjust to the warmth.

3. Sicaklik, also called harareth (Roman caldarium) is the hot room where the steaming takes place. An indispensable part of the sicaklik is a large dome. The dome has small windows that provide half-light. In the center of the dome there is a large marble stone called “cebec” or “gobek tasi” (hot stone). There are niches and fountains on either side of the cebek.

4. Halvet — a closed cabin for individual washing and massage.

5. Kulhan — a furnace that is located under the hammam.

6. The room for the furnace, firewood storage.

7. Toilets.

What do Roman and Turkish baths have in common? Unlike saunas and Russian baths, the furnace is not located directly in the bathing room, but under the floor. The Roman thermae used hypocaust (literally “heat from below”), a kind of central heating system.

The furnace heated air and water. In their turn, air and water moved through special channels in the floor and walls, and heated the premises of the bathhouse. There were also pipes for the removal of overheated steam and a fairly well branched out water supply network.

What about now?

There are still similar hammams, such as the beautiful Daut Pasha in Macedonia.

On the other hand, this former Tatar bathhouse in our country does not look so majestic, but still reminds us of its former glory:

I looked at this story and imagined that if I had some spare money, it would have been great to restore this wonderful bathhouse and steam in it with family and friends.

Although, who knows, maybe the money will come to hand ????